Chapter 3, Part 2 - Te Ao Nui a Tangaroa

The World of the Sea God Tangaroa

Please enjoy listening to horomona horo demonstrate the puaatara while reading chapter 3, Part 2.

In a myth which explains how the fish became so different from each other, sea creatures battled land creatures to establish their own domains. Crabs, and their relatives, the crayfish, left the family of legged land beings and most crabs now live on the seashore. Papākā , the crabs, have been adopted by Tangaroa since that time

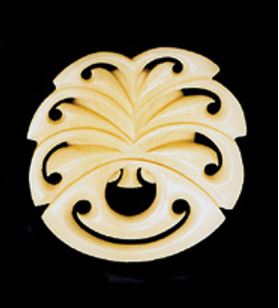

Two sides of crab carvings

Their tough armour, powerful pincers and ferocious appearance contrast with their comical, scuttling, sidewards gait, as they run to hide and survey the world with independently waving, periscope eyes. A view of the underside (previous page) celebrates the symmetry of their many legs, which resemble a kōwhaiwhai design. The crab also represents the star sign Cancer for many people, and is worn as a kaitiaki for that reason also. Here the manaia faces represent the gift of strength in its powerful claws. At the Portobello aquarium on the Otago Peninsula I once watched an octopus when a kōura , or crayfish, was put in its tank. The octopus stalked it and played with it like a cat with a mouse before eating it with obvious relish. But the crayfish is so much more than a delicacy for fortunate diners. In its ocean domain it has a stately demeanor and a fearsome presence. Its graceful, tapering antennae, its prominent, independently moving eyes and its stance on dainty toes are hallmarks of an aristocrat, an ariki of the marine world. After many years of constant wear the delicate carving below broke, so to strengthen it I had a craftsman jeweller encircle it with a band of silver, which beautifully complements the bone and made me think that I should have had it done when I first made it.

Koura carving strengthened with silver

The koura carving below was inspired by the ancient carvings generally ascribed to the Waitaha iwi, shown earlier in this chapter (see page 80). The traditional kaokao shapes have been adapted to form the many legs of this crustacean.

A koura carving based on ancient designs

It is always a challenge for me to reduce something to its essentials, while still keeping it identifiable as the complex being that provided the inspiration. I enjoy both the complex form and the distilled ones, but realise that sometimes I have the advantage of knowing the intermediate stages of a design, whereas others fail to recognise the image. This is however compatible with the tradition of knowing the story being told, where the image is a mnemonic to remind one of it

Two examples of a stylised koura design

I recently met Fumio Noguchi, who has emigrated from Japan and now lives not far from me, and we exchange books on Japanese art and take inspiration from each other. It has been interesting to watch his work develop, and his knowledge of Japanese culture helps me appreciate their carvings even more. Two examples of Fumio’s work are shown below. He carved the koura from the base or crown of a deer antler and then carefully stained it. It is quite a contrast to the stylised one opposite, but the circular form links them together. Fumio also carved the netsuke as a wheke (squid) from the tip of a deer antler, and its sheephorn eyes have a dominating glare that reflects the following legend.

The legend of Kupe, the great Polynesian explorer who came from Hawaiki to Aotearoa, tells how he was pursued by a giant wheke, which could be either a squid or an octopus. This ended in a great battle in Raukawa Moana (Cook Strait) where the wheke was slain, its legs severed and its eyes turned into two sentinel rocks, which remained so powerful that travellers who crossed the strait dared not look at them. Several other places in the area have names which remind us of parts of that epic story. The use of stylisation is the basis of the octopus carving shown below. The octopus’s large eyes and long, tapering tentacles covered in suckers are the aspects which created the greatest impression on me. Here they are represented impressionistically by spaces, using a process where stylised elements are reassembled to fit the design area, with some features omitted.

One particular type of wheke creates the paper nautilus, which is the most delicate of sea shells, with its fragile surface intricately sculpted. The contrast between its large opening and the symmetrical whorl that flows gracefully into it is sublime. Its Māori name, pūpū tarakihi, translates as ‘the shell like a cicada’, for its delicacy and function are mirrored by the moult case left by a cicada when it climbs from the ground to change into adult form. Another name, muwheke, acknowledges it as the egg case of an octopus. For me, the powerful appearance of the shell, contrasting with its extremely delicate structure, becomes a reminder of the fragile state of many beautiful things in nature, and the need to be careful they are not destroyed. Their existence enriches us, and wearing a representation of one reminds us how fortunate we are to have such special things around us

After observing the wide variety of būbū, or sea snails, that my grandson and I found in some rock pools, I tried to capture some images that reminded us of them and came up with the designs shown below. The face of the first one reminds us that this is after all a ‘snail person’.

As a boy I wondered why the kina was called a sea urchin, and it was years before I learned that the word ‘urchin’ is an archaic term for a hedgehog. It is therefore a very good description of this beautiful creature, whose shell is such an intricate work of art. Kina are mainly regarded as a prized delicacy by those who have acquired a taste for them, but to watch them moving around on the ocean floor is to witness a marvel, for hundreds of spiny legs on the outside of their shell work in a perfectly coordinated wave of gliding motion.

My brother-in-law, the late Captain Alan Kenning, who gave invaluable support to my work in the difficult early years, asked me to do a carving of the logo from a Canadian fishing lodge where he had stayed (below).

I enjoyed doing a more naturalistic representation of fish, and many years later I applied that to the three-dimensional carving shown below. The school of hāpuku, or grouper, was carved from a whale’s tooth that had sustained some damage, with cracks and corrosion in the tip and nerve cavity. I decided that the safest thing to do was a group of fish, as I could make adjustments in their size as required by the defects I knew I would find as I carved into it. Fortunately, to my relief, the defects all disappeared into the design as if part of the plan

In my research into traditional names for various types of whales, I found that while some species did not have one, the endemic Hector’s dolphin had five. This intimated to me that they have always been regarded as unique, and my mentor, Sir Tīpene O’Regan of Kāi Tahu, told me that tūpoupou is the name that appears most in southern accounts. My first encounter with them came while body surfing in Tewaewae Bay, on the south coast. I looked down to see a dark shape by my leg, and my first reaction was panic, as the area had a reputation for fierce sharks, but to my relief I realised it was a dolphin. My heart continued to race as a pair of tūpoupou surfed beside me in the swells, leaving me with a thrilling memory that has never faded. Using a small whale’s tooth for tūpoupou, and some whale jawbone for the waves, I captured those moments with the carving below.