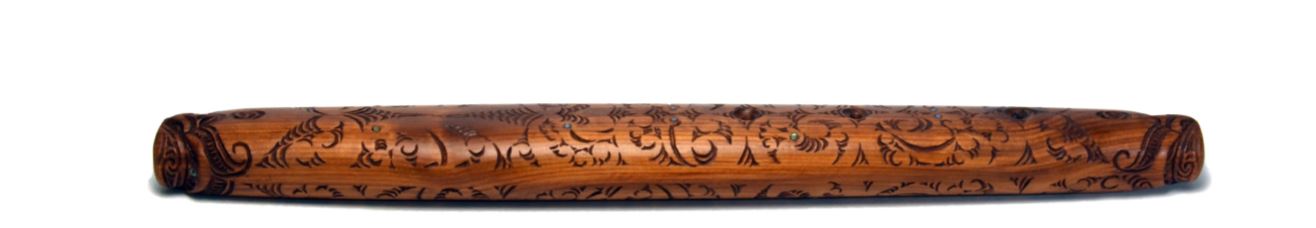

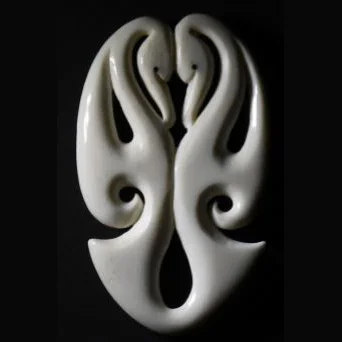

We start with Te Kore, silence and nothingness. It was the atua who sang the world into existence with the koauau and so it is with this music. The opening phrases are played on a toroa (albatross) ororuarangi, an instrument closely related to the koauau. With it, emerge the sound of Ranginui represented by air blown through a putorino and Papatuānuku represented by the grinding of stones. Ariana sings Io Whakatata, a waiata which refers to moving through different layers, coming closer, as in the creation myth. The emergence of Tane comes with the sound of the great tumutumu Te Waewae Tapu o Hinewaipupu, following which we hear Waraki, a dawn chorus, of manu which feature edge tones of putorino, karanga weka, karanga manu, karanga ruru, and hue puruhau. A second, whispered waiata by Ariana again speaks to the creation myth and is followed by a third waiata Te Haeata (the Dawn) with kupu by John Stirling. The original rangi to this waiata can be discerned amongst the cacophony of birdsong. A seascape of Tangaroa speaks to the great Waka Huruhuru as it sails to find (if there is) a way through the horizon. The rangi is played on a toroa (albatross) ororuarangi. But the discovery that lands exist beyond the horizon was not known by Māori alone. The next short section explores the first contact with pakeha in 1642 where a misunderstanding of the intentions played on instruments resulted in death. The pukaea and pupakapaka vie for ascendance and this is followed by a short rangi of the side blown putaratara. A disquieting stone-scape resonates with the taniwha Ngararahuarau, whose bones are strewn across the top of the Takaka Hill. The porotu Na Te Po Ki Te Ao brings peace again and maintains a sentry over the Mohua (Golden Bay). Ngā Hau E Wha (the four winds) features four purerehua accompanying Hirini’s waiata Purerehua sung by Holly. Hine Pū Te Hue, daughter of Tānemahuta and Hinerauā, brought peace to the fighting between the atua which resulted from the separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. She became the mother of the gourd family and here we hear a selection of gourd instruments including two poi āwhiowhio, hue puruhau and hue puruwai.