Chapter 3, Part 1 - Te Ao Nui a Tangaroa

The World of the Sea God Tangaroa

Please enjoy listning to 'hinemoana' by hirini melbourne while reading chapter 3, part 1

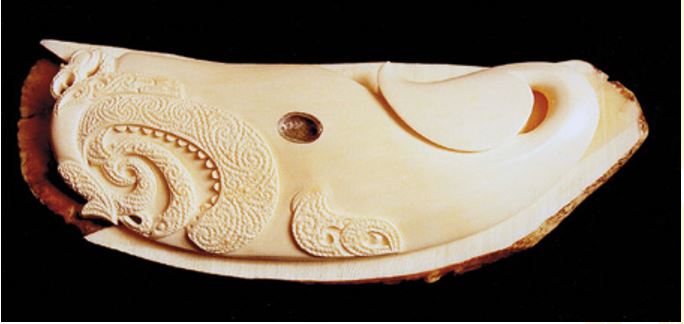

A carving from the jawbone of a sperm whale showing Tangaroa inspecting the artistry of a hei matau. The hook was let down to impress him so that he would reward the fisherman with a good catch of his children, the fish.

When I was about 10 years old our family moved from the city to the tiny seaside settlement at Colac Bay, near Invercargill. I now realise how important this was to my future life, because we lived next to my grandparents, who ran their subsistence farm in an old-fashioned way, using a horse and cart, and Grandad Coster’s inventiveness and independence shaped my attitudes. Most of my schoolmates were part Māori and I treasured my time there, though I think of it as Kōlako’s Bay, named after the chief who once lived there.

Colac Bay, Southland

We lived close to the beach and the rocky headland, and most of all I enjoyed exploring the rocky pools and fossicking for treasures among the tidal flotsam. There I found the opalescent pāua, treasured sea horses and numerous crabs and fish that I would rush home to ask about or look up the name of. Sometimes a black cloud of tītī, or muttonbirds, would drive frantic shoals of herrings right on to the beach, and occasionally we saw dolphins in the bay. From Hine Tui, the headland, we could see across Te Ara a Kewa, Foveaux Strait, to Rakiura, Stewart Island and I often gazed out hoping to see a whale spouting. From this special place I gathered a treasury of experiences, which have become a part of me and my carving. Though I have yet to see a whale from there, it is home to the myth of the great whale Kewa, the grandson of the ocean god Kiwa, after whom the Pacific Ocean is named: Te Moananui a Kiwa. It was Kewa who ‘bulldozed’ the path that is now Foveaux Strait when he became attracted to his beloved. She lived on the other side of the anchor rope for Aoraki’s canoe, which stretched across from Bluff to the anchor stone, Rakiura (Stewart Island). Whether he did it to impress her or to save the long, cold swim around the south of the anchor stone we are not told, but this stretch of tempestuous seas, though notorious for its currents and storms, has proved a convenient passage for mariners ever since. Apart from Niho Kewa (Solander Island), which is a tooth lost by Kewa when he opened the path between Bluff and Rakiura, the whale tooth opposite is the biggest I have ever seen. Its owner agreed that we carve half of it as Kewa and keep the other half to mount him on. This illustrates how little change had to be made to the original shape while creating a strong whale image with its face carved in a traditional wood carving style.

A whale tooth carved as Kewa

Sperm whale tooth, niho parāoa, is my favourite material to carve, and its scarcity makes it particularly precious. In fact, the first tooth I was given to carve by Tīpene O’Regan had to wait several years before I plucked up the courage to work on it. Now my favourite challenge is to carve a whale tooth into one of the family of whales and dolphins. These are collectively named tohorā, and are the eldest children of Tangaroa.

Sperm whale tooth carved into a whale

Sometimes I am amazed by the likeness to a whale that exists in both bones and teeth, a likeness that can be brought out with minimum reshaping, as in the previous two illustrations and also in the carving below from a humpback whale’s ear bone.

A pair of whale ear bones showing that the carved whale shape already existed in the raw bone

For a number of years I have been involved with our local iwi, and when strandings of the big whales occur we have the task of removing the bone for carving. While this is very traumatic because we all have great affection for these enormous beings, their sheer bulk makes survival impossible once they become stranded, as they sustain fatal internal damage from their own weight. We therefore focus on the fact that the stranding of whales is acknowledged by Māori as a special gift of his eldest children from Tangaroa, and it becomes our duty to honour that gift by removing their bones so that treasures can be created from them. In 1997 Hirini Melbourne, Richard Nunns and I were taken by the local iwi to play traditional instruments in a dawn ceremony at the farthest end of Onetahua, Farewell Spit. We were invited there because a part of the revival journey of taonga pūoro, the traditional instruments of the Māori, has been to play these ancient sounds again at sacred sites throughout Aotearoa. Shortly after this particular ceremony the stranding of five sperm whales occurred. This multiple stranding has been acknowledged by local iwi as Tangaroa’s endorsement of the revival of taonga pūoro, and so the legend of Hirini calling the whales ashore was born. This also acknowledges Hirini’s sharing of his affinity with nature, the wonder and beauty of its sounds and their relationship with the music, language and mythology that was instilled into him by his Tūhoe elders as he grew up in the Urewera bush. It was, therefore, appropriate for me to carve a tooth (below) from one of those whales, named Whaowhia, as a mark of this special stranding and the birth of a legend. The carving is both a whale and a nguru, or flute. The face of the whale is carved in a traditional style used for whales, and it incorporates the face of the flute itself, which has been named by Túhoe as Tútarakauika, which translates as ‘the leader of the pod’. The nguru’s tail flukes are decorated with manaia faces to acknowledge the gift of enormous strength they hold. The flippers are shown as hands to remind us that these are ‘whale people’ with a senior genealogy to us ‘human people’.

A carving from the tooth of a whale stranded at Farewell Spit

A whale-shaped nguru

The whale-shaped carving above is also a nguru-style flute, and though it is different in exterior shape from nguru in collections, the interior and finger holes are modelled on those older ones. Its shape was inspired by a copy I made of a partially decayed ancient whale tooth treasure (below) which had been improperly removed from a burial site near Kaikōura and taken to a museum. Its story was given to me by the local people when I took this replica back to them. For me this was a very emotional experience, and so I carved a similar niho parāoa into the nguru below.

Replica of an ancient whale tooth carving

Whalebone necklace from the Wairau Bar, now in the collection of the Canterbury Museum

Canterbury Museum has a collection of what are probably our earliest bone carvings, unearthed near Wairau in Marlborough, at the top of the South Island. These are now under the guardianship of local Rangitāne iwi who have given approval for their reproduction here. Generally they have been ascribed to the ‘Moa Hunters’, who were possibly the Waitaha people. Included in the artefacts are a number of ‘whale teeth’ necklaces. Some of these also appear to be highly stylised whales, and suggest a whale culture which may have given rise to the present belief that whales could be called ashore by a powerful tohunga or priest. Perhaps these necklaces represented the whales called by their wearer. They are certainly evidence of skilled craftsmen who created exquisitely simplified stylisations. Some of these early carvings have sharp edges that become rows of notches, and I observed when copying this style that the notching adds life and movement to the design. Their similarity of style to the Kaikōura treasure discussed on the previous page shows a common derivation. Interestingly, these are also similar to lei niho palāoa, the pendants of Hawaiian royalty. In 2009 I was commissioned to carve a presentation pair of pendants by Whalewatch of Kaikōura. They supplied a magnificent tooth from a whale named Hoon, who had been quite a personality during the early years of the whale-watching venture. Because the recipients had been founding directors of the business we decided it was appropriate to carve the tooth as a pair of whales (on the next page), as they were part of the creation myth for the South Island. Inspired by the surviving ancient treasures from the south I used some of those shapes to tell the story

A pair of whale figures carved from a tooth of the whale called Hoon

After the creation of the South Island from the great waka of Aoraki (see Chapter 1), Aoraki’s grandson, Tū Te Raki Whānoa, was sent to organise the reshaping and planting of the waka as a suitable habitation for humans. Many of the gods assisted in the huge task, part of which saw the Canterbury plains raked out, with the creation of a special fishing station now known as Kaikōura. Ever since then, Tū Te Raki Whānoa and Tangaroa, in the guise of two whales, have made occasional visits around the southern coast to keep an eye on their creations. The carvings opposite depict this pair. Tangaroa is the senior, denoted by the extra kaokao symbols he carries. These are symbols of strength and on the top they portray both the ribs which protect the body’s vital organs and the great feats these two are known for. Underneath they depict the whale’s flippers, repeated to show that many visits have been and will be made. The whale’s vital breath or spout is shown trailing from the nose. The wake of its passage flowing along each side is composed of whakapapa notches, which denote the countless people who have enjoyed their creation and can also represent the special people remembered by the owners of the whale carvings. The same story of Tangaroa and Tū Te Raki Whānoa inspecting the southern coastline is the basis of the paired pendant below. In this case I have depicted the whales by carving only their heads. Because some of the stories of their visits tell of them being close to shore I gave them large jaws with baleen plates hanging down, because tohorā, the right whales, often come close to shore.

A paired pendant representing Tangaroa and Tū Te Raki Whānoa

This carving was strongly influenced by the paired artefact over the page, as I have found that working this way sometimes helps me to understand the original. Perhaps that is because for many, many hours as the work is planned and then proceeds I am completely involved, and constantly thinking about both the piece and the traditional carvings that inspired it. Occasionally this leads to alterations as the carving proceeds

A pair of early whale tooth carvings from the collection of Te Papa Tongarewa

This pair is of early origin, and their intricate form is particularly interesting as most similar surviving carvings are even more broken than these. The two pendants carved from Hoon’s tooth are inspired by a style of whale tooth carving like this. I revisit their image quite often because, for me, they are a strong source of inspiration. Their artistry and workmanship are superb, and it is intriguing to puzzle over their original form and stories. Wondering about the stories behind the twin images of the old carvings led me to think about how different cultures portray similar concepts in a variety of ways. Even before I was carving seriously I saw an amazing Inuit carving of a polar bear looking at its reflection in the ice, and the idea appealed to me. I have always been fascinated by reflections, and so I decided to carve a series of creatures looking at their own reflections to develop this idea. Some examples of this series are illustrated opposite.

A fish looking at its reflection. The reflection is carved in the old Māori style, with dorsal fins represented as stylisations of face profiles.

For this carving I imagined a manaia (sea horse) that had been captured and brought into an aquarium. It has swum to the glass wall and sees what it must think is another sea horse.

This dolphin is seeing its own reflection

Reflections are reversed images, and I have expressed that here by reversing them in a different dimension. This dolphin is seeing its own reflection as it leaps above the calm sea – a twist of perception typical of the small touches of humour in Māori carvings that I really enjoy.

Old recycled billiard ball

The opportunity to recycle this old billiard ball allowed me the freedom to work in a more three-dimensional form, and I attempted this frog looking at its reflection, inspired by the work of the great Japanese netsuke carver Masatoshi. (It was several years later before I could complete it as I had dropped one of its ram’s horn eyes and kept hoping that I would find it.) The dolphin design opposite had its origins when I was doodling with a yin– yang design, and thinking of its similarity to the Māori Ira Atua–Ira Tangata concept mentioned earlier. I whimsically mused that a great whale moving through the world’s oceans would be oblivious to these human concepts, and then saw that by shrinking one half of the yin–yang design and stretching the other to join it, the profile of a whale was created. The pleasing shape created in the centre meant that the original concept of balancing halves was retained, but expressed in a Māori style. When both sides of the design were joined together a whale tail shape was perfectly formed and the addition of flippers completed the design (below).

Two whale carvings derived from a yin–yang design. The incorporation of traditional features on the face, with the flippers depicted as hands, gives a more traditional appearance

I was so excited by this development that I continued to doodle and found that if I turned the whale the other way up, with only a few alterations it became a dolphin (below). This ties them both into the same family, which is how they are traditionally classified by Māori. Two further examples illustrated below show how I have extended the design to include the addition of a baby, and suggested a reflection, as on page 81. I enjoy playing with a design concept in this way to create design families.

Three tohor ā carvings derived from a yin–yang design

The whalebone piece below was presented to Queen Beatrix of Holland by the iwi of Onetahua (Golden Bay) during her visit there in 1992. I chose these dolphin images to represent the historic meeting of the two cultures when Abel Janszoon Tasman anchored in the bay in 1642. It has been speculated that the playing of a pūtatara (conch trumpet) and the reply from the ship on a bugle was interpreted by the Māori as a challenge, which led to their lethal attack on a ship’s boat the following day. By portraying the dolphin in two ways, the carving illustrates how different our perceptions of the same thing can be.

This carving of two dolphins represents the meeting of two cultures when Abel Janszoon Tasman anchored in Golden Bay in 1642

Another fascinating inspiration came from viewing a picture of an oriental carving in the book Jade, edited by Roger Keverne. The broken jade dragon was probably made about five thousand years ago, and I wondered how the complete carving would have looked. I added a tail to my sketch of it and gradually it evolved into the manaia, or sea horses, shown below. Years later a Chinese visitor told me that their name for sea horse translates as ‘the love child of a sea dragon’, which is certainly an apt description that suits both sea horses and the development of this design. My fascination with sea horses began, as I mentioned earlier, when I pulled a piece of floating seaweed into our dinghy at Colac Bay and then noticed something tickling my toes. I was hooked on this mystical creature that moves through the water with such aristocratic grace, and now my gallery is never without at least one sea horse carving. The pair below were carved from two very large wart hog tusks, and I was pleased that, despite being much simplified, they remain distinctively sea horses – interestingly, they look even more like the jade dragon than my earlier idea.

Sea horse carvings inspired by an oriental jade dragon

A pair of sea horses carved from wart hog tusks

An old sea-worn piece of whalebone seemed just right for the sea horse shown below, and two tiny pāua shells I had collected decades earlier from a beach on the shores of Foveaux Strait became its eyes. Its bearing reflects the status of its Māori name, manaia, which bestows status. Because the sea horse uses its tail to hold on to things, in this carving I depicted its tail as a hand

A whalebone carving of a sea horse

I think that the pair of sea horses on the opposite page are my favourite so far. They were carved from a section of the leg bone from a very large bull, and their sparkling pāua eyes represent perfectly those of a pair I watched one day as they swam in a rock pool and siphoned food from the sand.

A pair of sea horses

When I carved the whai, or stingray, below from a whale vertebra I didn’t think anybody would recognise what it represented, but my grandson took one look and said ‘That’s it!’ Not long before, we had been spearing flounder one night when we saw a large stingray between us and the shore, filling the whole of the area lit by the lamp. Because it seemed so huge my grandson immediately scrambled all the way up onto my shoulders – fortunately we already had two flounders for the next day’s breakfast, as there was no way he was continuing the expedition.

A stingray carved from a whale’s vertebra

Four carvings representing stingrays

I still carve whai because of the thrill of seeing them in the bay while kayaking. Watching their flight through the sea is aptly described as ‘poetry in motion’, and their fearsome side is easily forgotten. For some people the whai is a kaitiaki or guardian figure, especially for those who have a fighting spirit but live with confident serenity in their daily lives. In the carving below the wings are shown as manaia faces to acknowledge their power, and the barbed sting under the whip-like tail shows through the centre.

Stingray carving with manaia faces on its wings